Dealing with Agrarian Crisis or Hoodwinking Farmers Vikas Rawal

The agrarian sector of the economy has been suffering from an intense crisis over the last four years. The agrarian distress, whose origins lie in long-term neglect of agriculture particularly after 1991, intensified greatly over the last few years because of adverse impact of a series of decisions taken by the NDA government. Government policies over the last four years show an unprecedented level of neglect towards agriculture and farmers. Having capitalised on the poor performance of the UPA-II government in addressing concerns of the farmers, the NDA government only went on to further neglect agriculture and the rural economy. Worse still, several decisions have been taken by the present government to benefit big corporates and agro-business companies at the expense of farmers. Agricultural insurance was opened to private sector and a huge largesse has been given by the government to insurance companies in the form of premium payments while farmers have got little compensation for crop losses. While corporate fraudsters have milked the pubic sector banks dry, bringing many of them to the brink of a collapse, not even peanuts have been offered to farmers reeling under debt. There are no government controls on prices of seeds, pesticides and other plant protection chemicals, and fertilisers other than urea. Agro-business companies are free to set prices of these crucial inputs, many of them patented and produced by large monopoly transnational corporations, at whatever level they like. While global oil prices have remained low for most part of the last four years, government has used it as an opportunity to mop up excise duty and fund tax breaks and largesse given to big corporates. This has meant that prices of diesel — a key agricultural input for running pumps, tractors and other machinery — have remained high, and increased more than even prices of petrol, despite the global oil prices having fallen.

Along with these, recent years have seen a sharp deceleration in the minimum support prices (MSP) announced by the government. The rate of increase of MSP started declining during the UPA-II period, and fell further in the first four years of the NDA government. Apart from the MSP, actual prices received by farmers are determined also by demand-supply imbalances, policy decisions (demonetisation, for example), and behaviour of large monopsonistic buyers (millers, big traders, agro-business companies). Agricultural markets are highly imperfect, and these imperfections work to detriment of poor and middle peasants. All of this has meant that, while cost of production has risen sharply, the increase in prices farmers receive for their produce has not been commensurate, and returns they get have fallen in real terms. What we need to understand is that the income of an average farmer from agriculture is very low, and inadequate for even minimum level of subsistence. Also, obviously, an average is an average, and a large proportion of farmers get below-average returns. In fact, even official data show that, in any given year, a significant proportion of farmers incur losses.

The agrarian crisis has been further exacerbated because of government’s undermining agricultural research and promotion of unscientific practices. The National Agricultural Research System, which has played a stellar role in technological modernisation of agriculture over the last five decades, is reeling under fund cuts and restrictions on cutting-edge research (and field trials). While introduction of modern technologies is left to agro-business companies, government is busy promoting dubious farming practices that are backed by little scientific evidence. These include mandatory coating of urea with neem oil, promotion of chanting of mantras in the fields, and promotion of unproven remedies (like spraying gaumutra) to deal with pests and crop diseases. Restrictions on sale of farm animals, through a government decision that had to be withdrawn because of intervention of the courts and as a result of unchecked terror of cow vigilante groups, have meant that prices of livestock have fallen and farmers are forced to incur expenses to maintain unproductive animals.

It needs to be understood that this economic crisis of agriculture is a result of a multi-pronged policy neglect. While the decline in farm profitability is the key problem, deceleration of MSP is only one of the causes of it. Recommendations of the M. S. Swaminathan Commission, which has been much talked about lately, dealt comprehensively with various dimensions of the crisis that Indian agriculture faces. Of a wide range of these very important recommendations, one that has been specifically a focus of attention was that the MSP should be set to provide 50 per cent return over cost of production.

Earlier this year, the Finance Minister Mr. Jaitley declared that the MSP declared by the government was already 50 per cent above the cost. This was shown to be untrue and based on statistical jugglery, as the government decided to use a lower benchmark of cost (A2+FL) than C2, the measure of total cost of production used by the Commission of Agricultural Costs and Prices.

The latest decision to increase the MSP needs to be seen in this light. In particular, following points have to be noted.

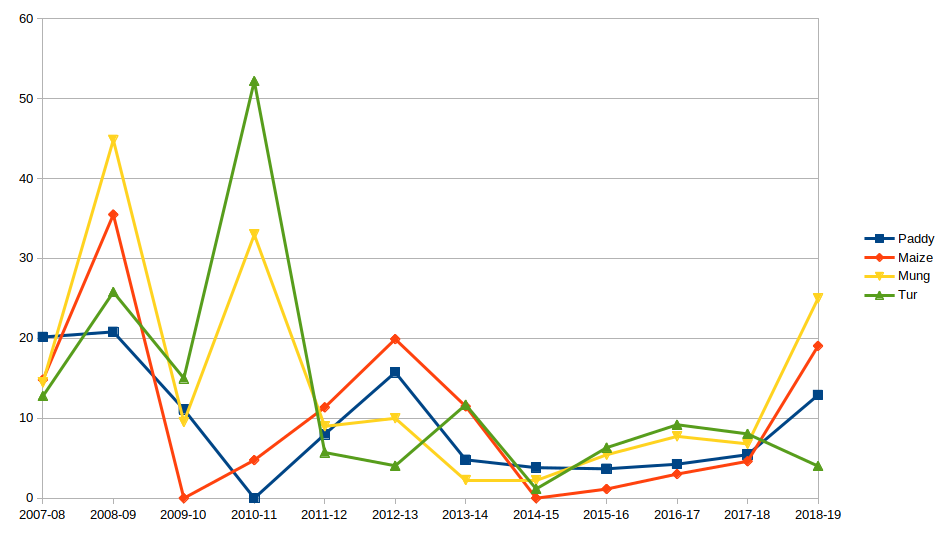

First, although the increase in MSP seems substantial in comparison with very little increase that has taken place over the last four years, the increase is nothing extraordinary and far from being historic (Figure 1). The price of paddy has been increased by about 13 per cent. In comparison, the MSP of paddy was increased by 20 per cent in 2007-08 and 2008-09, and by about 16 per cent in 2012-13. Price of maize has been increased by 19 per cent; in comparison, it was increased by 35 per cent in 2008-09 and 20 per cent in 2012-13. Similar is the case with most other kharif crops.

Secondly, the increases in MSP of pulses announced are very curious. The MSP of Arhar (Tur) has been increased by just 4 per cent, less than the increase even for last three years. Moong and Urad, both pulses belonging to Vigna genus, have very similar cost of production and yields. In the past, the MSP of the two crops has been similar if not exactly same. However, while the MSP for Moong has been increased by 25 per cent, the MSP for urad has been increased by only 3.7 per cent.

Thirdly, although the Government has claimed that the MSP is 50 per cent above the cost of production, they have once again used A2+FL cost to make this claim. It may be noted that A2+FL cost does not account for the cost of farmer’s own capital. Even when compared to official estimates of cost of production (C2), the announced MSP is only 12 per cent above the cost for paddy, 15 per cent above the cost for Maize, 12-14 per cent above the cost for pulses, and 14 per cent above the cost for cotton (Table 1). This is far from being consistent with the recommendation of the MS Swaminathan Commission.

Table 1 Difference between cost of production (C2) and MSP, major kharif crops

| Crop | Cost of Production (C2) | MSP | Percentage difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paddy | 1560 | 1750 | 12.2 |

| Jowar Hybrid | 2183 | 2430 | 11.3 |

| Bajra | 1324 | 1950 | 47.3 |

| Ragi | 2370 | 2897 | 22.2 |

| Maize | 1480 | 1700 | 14.9 |

| Arhar | 4981 | 5675 | 13.9 |

| Moong | 6161 | 6975 | 13.2 |

| Urad | 4989 | 5600 | 12.2 |

| Groundnut | 4186 | 4890 | 16.8 |

| Sunflower Seed | 4501 | 5388 | 19.7 |

| Soyabean | 2972 | 3399 | 14.4 |

| Sesamum | 6053 | 6249 | 3.2 |

| Nigerseed | 5135 | 5877 | 14.4 |

| Cotton (Medium Staple) | 4514 | 5150 | 14.1 |

Fourthly, although minimum support price is supposed to be the price at which government offers to buy the commodities if market price falls below this threshold, in practice, government procures only a few commodities and only a part of what is produced by the farmers. A vast majority of farmers, in particular those producing crops other than paddy in the kharif season, have to sell to private traders. These farmers do not benefit from the price guarantee that the MSP offers. Unless government commits to buy the produce at the MSP, announcing a higher MSP brings little benefit to a vast majority of producers. At the moment, government does not even have the infrastructural capacity to procure the produce if it had to actually treat this price as a minimum support.

More fundamentally, however, announcing a higher MSP may not bring any economic benefits unless government also works to check the increases in cost of production. In fact, any gain on account of increasing the MSPs will be eroded by increased cost of production and increased price of food unless complementary action is taken to check these. Bringing down cost of production — by way of increasing public expenditure on research, re-introducing price controls, expanding public-sector production and subsidising key inputs — is a far better way of making agriculture remunerative. Given a highly skewed distribution of land, a majority of rural households are net buyers of food. It is only by bringing down the cost of production that the government can simultaneously ensure that farmers get decent incomes and prices of food remain low for consumers.

The fanfare with which government has announced this rather modest increase in MSP suggests that this is little more than a tactic to hoodwink farmers in an election year. There is little chance that this by itself will do very much to solve the intense agrarian crisis that farmers have been facing for the last four years.