Export boom over, incomes take a dive for farmers in Rajasthan | Hindustan Times

Off a tolled highway in Rajasthan’s Sikar district, Tulcha Ram, a brawny 50-year old, offers a guided tour of his resplendent farm – one that may not remain his for long.

“Those are khejri trees,” he says, pointing to an elegant grove of prosopis cineraria with antler-shaped branches, all of similar height. The farm’s floor is iridescent-green and spongy as you walk it. It’s actually a month-old black gram or channa crop. Ram risks losing this bucolic haven measuring 3.72 hectares to his creditors.

A loan of Rs 3 lakh taken on Kisan Credit Card from the Punjab National Bank’s Badalwas branch in Sikar district turned into a Rs 4.5 lakh monster after repeated defaults.

“It was like a noose around my neck,” he says, showing off a notice issued on February 9, 2017 from a local official in Dhod tehsil to auction his land to the highest bidder. An auction fee of 5% was also added to the outstanding. Then, the bidding took place.

One-third of the total land holding – which is Ram’s share in the family property — was auctioned at Rs 18 lakh to the highest bidder, Nandlal Chawla from a neighbouring town.

Just as the auction proceedings were being closed, Ram showed up to pay the debt. He had collected the outstanding by “begging and borrowing” from everyone he could ask for help. Effectively, that was a loan to repay another loan. At the behest of local elders, the auction was reversed, he says.

Ram isn’t off the hook yet. “Now, I worry about paying all these creditors who helped me save my land from Punjab National Bank,” he says.

Farmers in many states have got into precisely these sorts of debt traps – a generic problem caused by high costs of cultivation and falling returns from agriculture. In state after state, governments have succumbed to pressure and waived off farm loans or are considering doing so. Maharashtra, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, and Karnataka have waived off loans, or partially written off loans, or part of the interests.

On February 12, Rajasthan announced it would partially write off loans owed by small and marginal farmers worth Rs 8000 crore. Its decision was forced by an 11-day protest by farmers in Sikar, 200 km from capital Jaipur from September 1-13 2017, last year.

“History shows that an agitation launched from Sikar never fails. It has always spelt trouble for governments. It is a revolutionary place,” says Amra Ram, the leader of All-India Kisan Sabha, who led the agitation. The siege was intense. Highways were blocked. Traders shuttered shops and transactions in the Sikar farmers’ market ground to a halt. Thousands from all over the politically influential Shekhawati region – comprising the three big districts of Churu, Sikar and Jhunjhunu – joined in. Amra Ram says the loan waiver will cover only 2% of the farmers caught in debt traps.

In 2000, the Kisan Sabha forced the government to release more power to farms. In 2015, it forced the then government to roll back electricity tariff hike after a 15-day protest, just like it forced the current government to defer a decision to raise rural electrify prices in 2016.

“What made last year’s agitation successful was that everybody joined us, even local DJs, with their fan following,” says Ram Ratan, a prominent farm leader from Sikar. ‘DJs’ bring to mind hip jockeys in city nightclubs, but in the Shekhawati region, they are local Jat youth who play ear-numbing music in local marriages, religious festivals, birthdays and other rural events from atop specially modified pickup trucks. When harvests are good, they make good money. When onion prices crashed in Sikar – the biggest growing district in Rajasthan – even DJs were without business.

The Rajasthan government’s loan waiver, limited to small and marginal farmers, is a follow up on an agreement it had signed with protesting Sikar farmers.

It promises to pay off Rs 50,000 of each small farmer’s total outstanding on short-duration loans taken from cooperative banks. The first test of whether this has managed to placate farmers took place on February 22. The main farmers’ body that staged the massive agitation last year, forcing the government to accept its demands, called for a similar agitation on that day. It believed the waiver wasn’t enough because it takes care of just 1 of its 11 demands. Its major demands were a total loan waiver, not partial, of all categories of farmers and a complete freeing up of cattle trade in the state.

Despite a loan waiver, hundreds of farmers blocked the Bikaner-Agra national highway 52 near Sikar town on Thursday. Two days ago, the government arrested the national secretary of Kisan Sabha, Amra Ram and his colleague Pema Ram, to pre-empt the protests. “Our leaders were arrested when they were on a padyatra (protest march) in Jaipur,” Ratan, their colleague said.

With elections due later this year in the state, the government is watching the farm sector closely.

“We need to understand that Rajasthan is neither Gujarat, nor Maharashtra. Rajasthan’s economy is mostly about tourism, mines and agriculture. I don’t think disruption from policies such as the Goods and Services Tax is an issue here unlike in Gujarat, which is a textile hub,” says Prof. Sanjay Lodha of Udaipur’s Mohanlal Sukhadia University. “The plight of farmers is because they haven’t been getting good prices,” Lodha says.

Just a few years ago, things were smooth-sailing. The rough patch in Rajasthan’s agriculture began roughly four years ago. Incredibly, a fracking boom in faraway US — which saw a surge in natural gas production to offset rising oil prices — brought prosperity to Rajasthan’s poorest farmers.

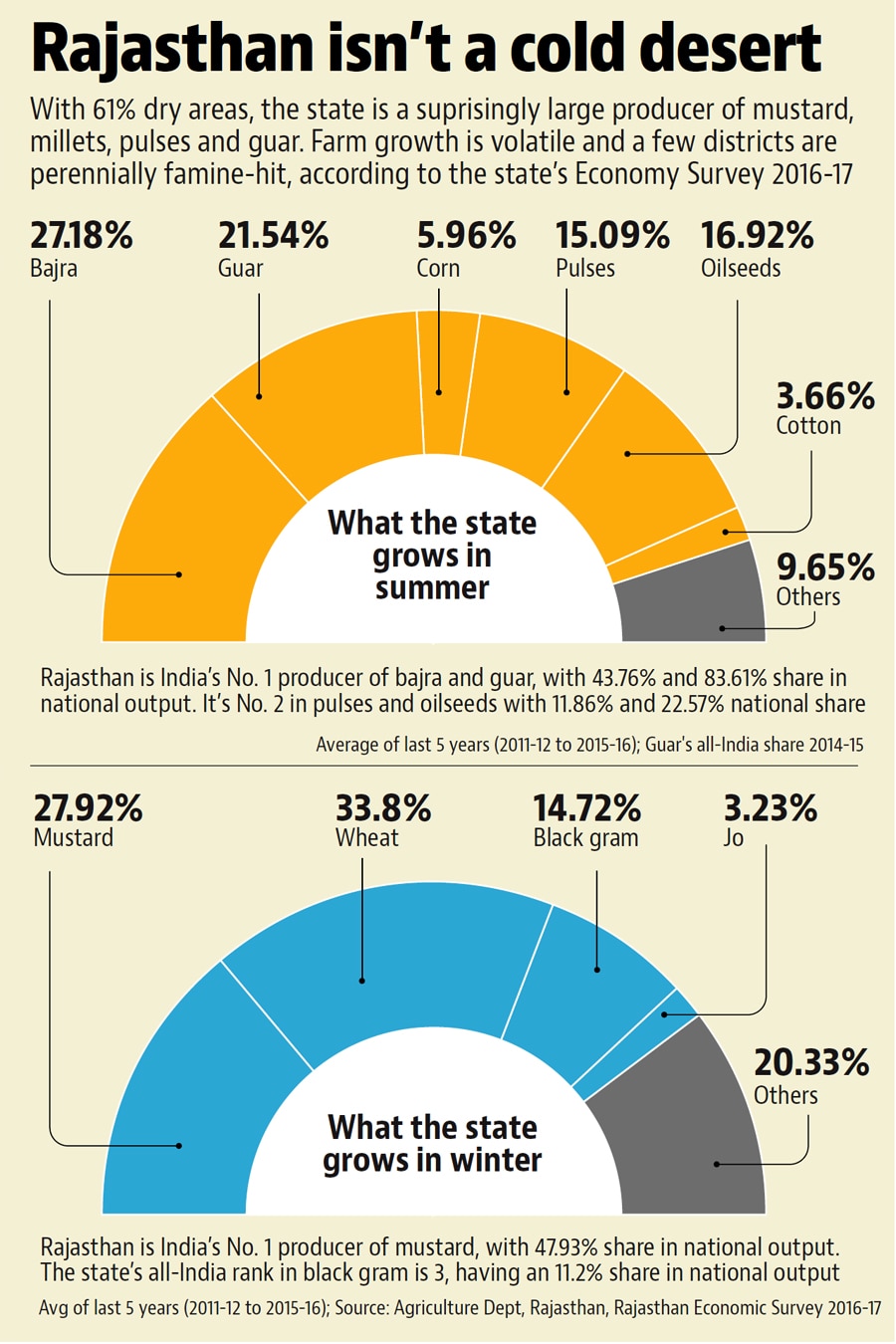

Fracking is a method of extracting shale gas by pumping high-pressured gas into the ground, which requires a processed powder called guar gum made from guar (cluster beans). Rajasthan is India’s largest gaur producer, with a share of 84% in national output. At its peak, the total export value of India’s guar gum – most of it from Rajasthan – rose to Rs 21,287 crore from about Rs 121 crore in 2003-04. In 2016-17, this came down to just Rs 3,106.62, an 85% fall.

The boom ended but farmers got used to better lifestyles. They bought cars, tractors and jewellery. The boom was over in 2012-13. What followed were two years of drought beginning 2014-15. “Farmers were already in distress. They got angry when they heard the government was going to increase power tariffs,” says retired bureaucrat Shankarlal Choudhury.

The pastoral economy has also been hit by self-styled cow vigilantes.

Laxman Singh, a livestock farmer in Dujod village, says income from cattle trade has dwindled because of cow vigilantism. “Milch cattle were like ATMs. If I need money, I just sell them. There’s hardly any buyer now,” he said. The government has tried to do its bit. Agriculture minister Prabhulal Saini says the government procured pulses, soyabean and peanuts worth Rs 2,800 crore at minimum support prices.

Rajasthan has also promised 6 months of free cow feed to cow shelters worth Rs 50 crore and help set up biogas plants in 25 identified large gaushalas with a subsidy of Rs 40 lakh for each. It is banking on these measures ahead of the crucial poll that will decide the fate of the Vasundhara Raje-led government.

The farmers are still unhappy lot. There are stuck on a demand for a total loan waiver. Ratan says he and others have forcibly put off auctioning of 122 land-holdings in Sikar, none of which will be benefit from the current loan waiver because they aren’t small farmers.

Source: Export boom over, incomes take a dive for farmers in Rajasthan | india news | Hindustan Times