Why Shekhubai marched Kavitha Iyer; Photographs: Amit Chakravarty (The Indian Express)

For the thousands of farmers from Maharashtra’s tribal districts who walked to Mumbai, the demand for land ownership is tied to their hopes for a better life — that they can dig wells, take loans and live without the fear of eviction. “We went for our stomachs,” they tell

Shekhubai, 65, joined others from her village Warkheda on the march. En route, her slippers broke and she had to get her feet bandaged. (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)

Shekhubai, 65, joined others from her village Warkheda on the march. En route, her slippers broke and she had to get her feet bandaged. (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)

Poatat bhukechi roz kaau-kaau re

Jungle cha raja haay tujha naav

(That’s the daily rumble of hunger in your belly

And you’re called the King of the Jungle.)

ALKA Dilip Mali, 36, breaks into a song to explain why she and 50-60 other residents of Pachewad Vasti in Nashik’s Chandwad taluka walked nearly 200 km to Mumbai last week. All the women in this hamlet have tales to tell of the six-day ‘Long March’ — of saris that turned a deep black with soot and cement dust, of broken chappals, of blistered feet and pus-filled corns and calluses, of cellphones that died and left them without even a brief conversation with the children back home. But their recollections are also of hope — when Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis announced that his government would attempt to resolve bottlenecks in implementation of the Forest Rights Act, 2006, within six months, the grime and exertion seemed worth it.

So it’s natural that Alka’s song is both a paean and an elegy, in equal measures a doff of their red Communist Party of India (Marxist) caps to one another’s hardiness and a sombre acceptance of their continuing struggle.

That’s also why just days since returning from Mumbai after what was declared a “historic victory”, tribal communities like the 70 or 80 families of Pachewad Vasti have begun to discuss the road ahead.

CPI(M) flags flutter across Pachewad Vasti and other remote villages of Nashik; like most families in Phopsi village. (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)Called by the CPI (M)-affiliated All India Kisan Sabha, the march to Mumbai demanded action on, and received assurances on, a wide range of agrarian issues, from a more extensive crop loan waiver to an overhaul of river-linking projects. But 90 per cent of those who participated in the march were tribals, almost all of them landless, and therefore holding no crop loans. Their demand was implementation of the Forest Rights Act, 2006, and specifically that they be given individual land titles or pattas for forest land they have cultivated for decades.

CPI(M) flags flutter across Pachewad Vasti and other remote villages of Nashik; like most families in Phopsi village. (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)Called by the CPI (M)-affiliated All India Kisan Sabha, the march to Mumbai demanded action on, and received assurances on, a wide range of agrarian issues, from a more extensive crop loan waiver to an overhaul of river-linking projects. But 90 per cent of those who participated in the march were tribals, almost all of them landless, and therefore holding no crop loans. Their demand was implementation of the Forest Rights Act, 2006, and specifically that they be given individual land titles or pattas for forest land they have cultivated for decades.

Maharashtra’s overall implementation of this law — enacted in 2006 to accord forest-dwelling communities legal rights over forest produce that has traditionally been a source of their livelihood, and a legal title for the land they live on and till — is leaps and bounds ahead of other states. However, there are wide disparities in implementing the law, and lakhs of tribals have waited years for the process of measuring their land and verifying their claims to be completed.

Now, as they prepare to seek updates on their applications for the land titles, those who returned jubilant from Mumbai are at pains to point out that ownership of land is only a means to an end.

“If we get patta, we can dig wells without fear that the boring machine will be seized by forest officers. We can take loans to invest in modern farming techniques, we can build water-storage structures that will help us all year-round,” says Hanumant Gunja, 39.

Shantaram Jhople and wife own 10 acres, but the output and quality of produce are poor (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)If they manage to undertake farming through the year, they would be less nomadic, and could become beneficiaries of various government schemes for farmers.

Shantaram Jhople and wife own 10 acres, but the output and quality of produce are poor (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)If they manage to undertake farming through the year, they would be less nomadic, and could become beneficiaries of various government schemes for farmers.

But for now, 12 years since the law was enacted, Pachewad Vasti’s men and women spend two to three months of the year in Niphad, about 25 km away. Some find work harvesting the summer onion crop, others work as labourers on construction sites or at the agriculture markets, loading and unloading farm produce.

“Just when the children’s exams are coming up, we go off for months, leaving them in the care of others,” says Ganpat Gunja, Hanumant’s brother. The lucky ones are paid Rs 150 a day. Others have to earn their pay by tonnage — for example, Rs 60 for sealing and loading on to a truck ten 10-kg gunny bags of onion. That money is saved up painstakingly and re-invested in farming, but theirs is a hardscrabble cycle of despair.

Three years ago, when a hailstorm and heavy rains uprooted a gnarled old tree in Pachewad Vasti, the Forest Department sent men and machinery to chop up the large blocks of wood and cart them away. “The hailstorm damaged our homes, some roofs were blown away, our crop was destroyed, but officials did not even register our losses — it’s as if we and our world do not exist,” says Hanumant.

Barely a couple of hundred metres behind their mud homes is the unyielding rock face of the Satmala hills, a sheer climb to a series of historical forts. Vegetation is sparse, but there is a perennial mountain stream that ends in an eight-foot-wide pond. This, and a private land owner’s well, are the only sources of water.

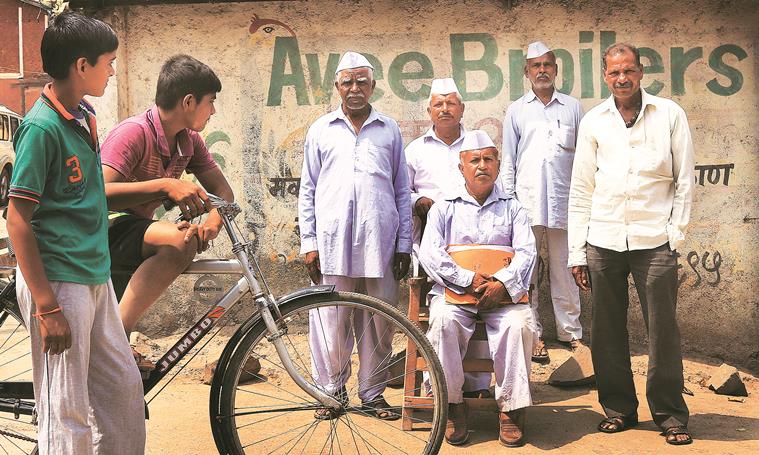

The march to Mumbai was organised by CPI(M)-affiliated All India Kisan Sabha (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)There is a twin-seat toilet block built under the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, but it has no water. The nearest school is a 2.5-km walk away, past a river that floods during the monsoons and keeps the children home.

The march to Mumbai was organised by CPI(M)-affiliated All India Kisan Sabha (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)There is a twin-seat toilet block built under the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, but it has no water. The nearest school is a 2.5-km walk away, past a river that floods during the monsoons and keeps the children home.

Pachewad Vasti’s 60 plot-claimants under the FRA have planted onion seeds, jowar, nagli, even some coconut trees, but everybody’s looking for work to make ends meet.

Sixty kilometres to the north-east of Pachewad Vasti is Dindori taluka’s Phopsi, another 100 per cent Adivasi village. Here, every morning, men climb aboard seven to eight crammed vehicles that ferry them to nearby towns and larger villages where labourers are needed. Families here have up to 10 acres each of forest land for farming, but it’s a measly crop, always sub par in terms of output and in quality of produce.

Here, Mirabai and Baburao Hire have some jowar on the field that Baburao is doggedly protecting from birds, but annual profit from their 10 acres has been less than Rs 10,000 for years now, worse in the drought years. In their sixties, the Hires still labour on others’ farms.

Last week, as Baburao stayed back to look after the grandchildren, Mirabai joined the ‘Kisan Long March’. She still has in a cloth pouch she wears on her hip the paracetamol tablets handed out by doctors in Mumbai when she took ill. “My elder son is a labourer in Nashik. His wife works in people’s homes. My younger son studied till Class 12, and now he’s a farm labourer here. If we get land in our name, we could get a loan and try to make a living as a family together, with better investment in the farm,” she says. “That would be a more dignified life.”

***

Seen through the prism of urban environmentalism, these communities demanding forest land for cultivation are imagined as encroachers, people who clear thickly forested areas and cause widespread denudation. But in the worldview of Maharashtra’s Katkaris, Mahadev Kolis, Gonds and Bhils, this deforested land is their aai or mother. Their methods of cultivation are largely devoid of chemical fertilisers; they draw out no ground water. In these largely impoverished villages and hamlets, there is little or no mechanisation in farming.

Ask how their crop survives without irrigation, and they point a finger skyward and say, nisargawar, that it is left to nature. They talk candidly of their own disturbance of the forest ecosystem, and say their occupation of these lands is neither for pleasure nor wealth, but for subsistence.

Maharashtra’s forest cultivators’ struggles date back to pre-Independence when land was demarcated for timber plantation. In the 1970s, activists with organisations such as the Bhumi Sena and the Kashtakari Sanghatana mobilised tens of thousands of members of these communities, seeking that forest-dwelling people be given legal rights over the land they lived on and tilled. By this time, the idea of a satyagraha or occupation of such lands was also beginning.

Dattatray Thormishe, 63, is among 130 farmers whose application for individual land titles under FRA has been pending for about five years (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)These struggles were central to the countrywide agitations before the Forest Rights Act was passed and perhaps also contributed to Maharashtra’s relatively superior performance in implementation.

Dattatray Thormishe, 63, is among 130 farmers whose application for individual land titles under FRA has been pending for about five years (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)These struggles were central to the countrywide agitations before the Forest Rights Act was passed and perhaps also contributed to Maharashtra’s relatively superior performance in implementation.

A 2017 report by the non-profit Community Forest Rights-Learning and Advocacy Group says that across India, only 3 per cent of the “minimum potential” of Community Forest Rights (CFR) had been achieved in the 10 years since the enactment of the law. (‘Minimum CFR potential’ is forest land within a village’s revenue boundaries and therefore immediately recognisable. The ‘minimum potential’ achieved is the extent of this land that is transferred to forest-dwellers.)

At 18 per cent of “total potential” for CFR achieved, Maharashtra’s performance is better than that of all other states, but implementation has been patchy — as many as 21 districts showed zero implementation.

***

In Warkheda village of Dindori taluka, about 50 km from Nashik city, Shekhubai Pandharinath Wagle, 65, lives alone in a single-room structure built on the land she tills. There is no source of irrigation nor money to buy water. Her husband died many years ago. Her only daughter is married and lives elsewhere in the district.

Shekhubai is myopic, and has never been in the best of health since having to live alone. The income from the one acre of forest land she tills has dwindled to a few thousand rupees every season.

But she didn’t hesitate when people in Warkheda came to a loose consensus that every family would send someone to Mumbai on the long march. En route, when her slippers broke, she continued barefoot. By the third day, as temperatures neared 40 degrees Celsius, she was feverish and nauseous from the heat and hunger, and angry blisters ripped open her underfoot.

“I called MLA Gavit (Jiva Pandu Gavit, the CPI-M’s seven-time MLA from Nashik’s Kalwan constituency) and told him about her condition. He sent an ambulance to where we were,” says Sindhubai Gaikwad, 55, former sarpanch of Warkheda who participated in the march.

Villagers of Pachewad Vasti sing songs of their struggle to explain why they marched to Mumbai last week (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)Sindhubai sat with Shekhubai in the ambulance, where the latter’s feet were bandaged, as dozens of other villagers were handed out paracetamol tablets. “After some time, we continued. She walked with the bandages. A few hours later, she had to sit down again. We slowed down, but nothing was going to stop us,” says Sindhubai, who put her sons through school with their forest-cultivation income supplemented by daily wages as farm labour.

Villagers of Pachewad Vasti sing songs of their struggle to explain why they marched to Mumbai last week (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)Sindhubai sat with Shekhubai in the ambulance, where the latter’s feet were bandaged, as dozens of other villagers were handed out paracetamol tablets. “After some time, we continued. She walked with the bandages. A few hours later, she had to sit down again. We slowed down, but nothing was going to stop us,” says Sindhubai, who put her sons through school with their forest-cultivation income supplemented by daily wages as farm labour.

They had set out with one single meal — bhakri and chatni – wrapped in a muslin cloth. Also in the cloth bags they carried on their heads was one change of clothes and a plastic water bottle, that they would refill wherever possible.

Back home, residents huddled around the few TV sets, watching news round the clock, looking intently at faces in the crowd, hoping to catch a familiar face on camera.

Kusum Asavale, 42, was among those who stayed back to watch over the children. Her 24-year-old son was in the march, and his cellphone battery drained on the very first night out, and that was the last she heard from him through the next five days, her stomach knotting tightly as news channels began to bring images of protesters with injuries, heat stroke and exhaustion.

At 65, why did Shekhubai not choose to stay back? “Potasathi,” is all she says. “I went for my stomach.”

Warkheda’s 200-odd forest land cultivators have all submitted to the gram sabha their applications for individual land titles, as prescribed by the Act. The gram sabha had passed a resolution, giving its nod, and applications had been forwarded to the next level, the sub-divisional level committee (SDLC).

Nearly 70 claimants received land titles, while the others, among them Dattatray Thormishe, have not heard from the SDLC for at least five years now. The 63-year-old keeps his forest claim documents at the ready, including a primary offence report by the Forest Department accusing him of “encroaching” upon the land, and a conviction order dating back to the 1990s by a local court, that had sentenced him to two days’ simple imprisonment and a penalty of Rs 50.

Thormishe says almost everyone of Warkheda’s forest land claimants has evidence showing they have been tilling this land since pre-2005, an essential requirement under the Act to be able to claim land. The gram sabha nod came expeditiously. “It’s been stuck since then,” he says.

Baburao Hire and his wife Mirabai grow jowar, but make an annual profit of less than Rs 10,000 on their 10 acres (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)Geetanjoy Sahu, assistant professor at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences and one of the authors of the CFR-LA report, says delay by the SDLC in processing claims is a common complaint. While the law prescribes a 60-day period during which appeals have to be filed against orders of the gram sabha or the SDLC, the law has neglected to provide a time-frame during which these applications or appeals must be processed and disposed of. So appeals remain pending, sometimes for years.

Baburao Hire and his wife Mirabai grow jowar, but make an annual profit of less than Rs 10,000 on their 10 acres (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)Geetanjoy Sahu, assistant professor at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences and one of the authors of the CFR-LA report, says delay by the SDLC in processing claims is a common complaint. While the law prescribes a 60-day period during which appeals have to be filed against orders of the gram sabha or the SDLC, the law has neglected to provide a time-frame during which these applications or appeals must be processed and disposed of. So appeals remain pending, sometimes for years.

***

Across Maharashtra’s tribal districts, the protesters try to explain that their demand for patta is deeply connected to their lives.

In Phopsi, Anita Kuwar’s son dropped out after Class 9 a few years ago. It was a difficult time for his divorced mother, and he decided to do odd jobs to help. He is now a labourer, his education over for good. Anita herself studied till Class 5 in a tribal ashramshala, and now works with the CPI(M), besides tilling her 10 acres.

“But there’s never any money for doctors, nutrition. And if we fall sick, we have to go hungry unless there’s somebody else earning as a daily wager,” she says.

Her father had a cataract surgery, and the process of having him hospitalised and cared for, while their farm land lay neglected, has set them back by several months.

Above all, “more humiliating than anything”, as a woman in Chandwad’s Rasewadi hamlet says, there is the fear of eviction.

The 60-odd families of Rasewadi live in shanty-like structures built on forest land; they do no farming here. They are members of a nomadic community who have traditionally lived on landed farmers’ fields, where they worked in return for an annual payment. They arrived in Rasewadi in the 1980 and 1990s — either after being evicted over differences with their landlords or joining movements to occupy lands.

Almost every family here reports having paid money to continue living on this patch of barren forest land with no road or access to a water source.

“But we have never got a receipt. And even today, if we are caught bringing firewood from the hills, we are dragged off in a vehicle,” says Ujjwala Waghmare, 40. “We have job cards but no work under MGNREGA, we have no land, no water. It’s as if the entire land satyagraha was a waste.”

That’s why she went to Mumbai. “Parat ek satyagraha. One more satyagraha.”