Why Maharashtra farmers walked 170 km and how their strike played out

In the hilly terrain at the northern tip of Western Ghats, bordering Maharashtra and Gujarat, lies Surgana, an erstwhile princely state ruled by tribal chieftains of the Mahadev Koli tribe. Surgana joined the instrument of accession to be part of the Indian Union in March 1948. Seventy years later, in March 2018, it was the birthplace of the uniquely successful protest by the tribal folk and farmers of Maharashtra.

Minal Pawar, 32, and a graduate in commerce is the sarpanch (head) of the gram panchayat at Khobla village, 20 km from Surgana town in the northern district of Nashik in Maharashtra.

As she pulls her daughter, a toddler, to pacify her, she recalls how she led one group among the 25 that left from Nashik city on March 6. She took up the responsibility of leading farmers from six padas (hamlets) surrounding her village.

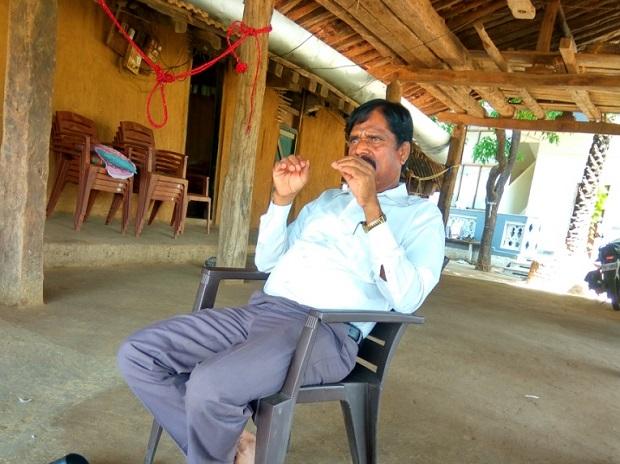

“When Gavit saheb informed us about the march, we spread the word to nearby villages in two days,” she reveals. Jiva Pandu Gavit, 67, member of legislative Assembly from the region since 1978 with brief interruptions, is a mass leader with a loyal support base and a strong organisation of volunteers in the tribal belt. He is the lone MLA of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) in Maharashtra.

The ownership of land being tilled for generations, pension for the old and subsidised food through the public distribution system have been the long-standing demands. Those leading the protest march added to this list their demand for loan waiver and remunerative prices for their produce.

“On the one hand, we cannot grow food even when the land is available, and on the other, we do not get subsidised food if the ration card is damaged or misplaced,” says Rahul Gavit, another young sarpanch of the nearby village of Hatrundi.

About 25-30 young workers like Minal and Rahul were given the job of leading a contingent of 500, and to ensure the availability of a water tanker and a pick-up truck for their group to carry daily essentials like rice, dal and oil, in addition to modest bedding for each of the members.

But this meticulous planning of making manageable groups of 500 each, entrusting the provision of food, water and bedding autonomously to a group leader, and continuous coordination between group leaders and march leaders was a daunting task, says Dr Ajit Navle.

Navle, 41, a general physician in Akole town in Ahmednagar district and the state general secretary of All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS), is one of the leaders of the protest.

“When you know that it is a fight for survival, mobilization does not need money,” he asserts. “Farmers and tribals have been looted for generations. We have marched to ensure ‘loot-vapsi’ and ‘loot-mukti’ of our people,” his voice rises.

About 300,000 farmer suicides have been reported in the last 20 years, which translates into 40 farmers ending their lives every day in India. Maharashtra, with more than 45,000, leads all states.

He believes that the farmers’ long march of March 2018 is markedly distinct from all farmer protests in the agrarian political history of Maharashtra. “Farmers’ movements till date were crop-specific. Late Sharad Joshi led massive rallies for cotton and cane farmers in the 70s and 80s, and underlined the importance of markets for farmers.”

“But this is the first time we gave a call to farmers across the state cultivating all kinds of crops, or even those engaged in non-crop activities like dairy and poultry,” he adds.

Growth in agriculture in a decade post-liberalisation had slipped to 1.74 per cent from 3.37 per cent ten years preceding liberalisation, a study by erstwhile Planning Commission had noted.

He, along with Ashok Dhavale, Kisan Gujar and Sunil Malusare—all of them members of AIKS and CPI (M)—traversed 25 districts of the state twice, once in February 2016 and later in April 2017 to bring voices of different farmers’ organisations together.

A member of the old guard of the CPI (M) from Maharashtra, Ashok Dhawale, 65, is a doctor by profession. He strongly believes that it was because of the incessant push from the Left that statutes such as the MGNREGA and Forest Rights Act (FRA) were legislated.

“This time, it is no different,” he says.

“The March 2016 ‘mahapadaav’ (mega gathering) in Nashik was the first successful protest in recent times. Then, both the October 2016 gherao of state-tribal minister’s residence—in Palghar, a tribal district north of Mumbai—and the May 2017 surrounding the house of agriculture minister—in Buldana district in Vidarbha region—got huge response from all kinds of farmers,” he explains the build-up of the protest over time.

The call for Bharat Bandh in June 2017—when farmers across Maharashtra refused to market their milk and vegetables—reached out to organisations like Shetkari Sanghatana from Western Maharashtra and Shetkari Jagar Manch from Vidarbha region, and culminated in the widely accepted leadership of Navle, Dhavale and Gavit—strong in the Nashik region, with support from organisations across the state.

At a meeting on February 16, 2018, at Sangli, the AIKS led by Dhavale, Gavit and Navle decided to march from Nashik, the hotbed of protests in the last three years, to Mumbai, the seat of the government, with at least 10,000 farmers.

Dhavale said that there were no corporate or political donations (from the opposition) to fund the protest. “We managed a part of it from concerned individuals, while most of it was borne by those who walked themselves,” he said.

Each group of 400-500 farmers was led by a small group of 6-7 people: leaders, drivers, scouts and cooks. The leaders collected raw food in the form of rice, dal and oil from the members themselves. The pick-up vehicle with scouts and cooks would leave early in the morning, visit a couple of places, finalise the place to rest and to eat and cook food in large containers for their group members.

“Only 70% of forest land claims in Surgana have been accepted, and to those accepted, only a portion of the original claim has been allotted. Some of them have received less than an acre,” says MLA and former AIKS state president Jiva Gavit.

‘Not holding or tilling the land in 2007’, when the rules of Forest Rights Act was framed, or ‘not entirely dependent on forest land for survival’ were the reasons given by the forest department while rejecting land claims.

“Had traditionally utilised lands been allotted and had the water flowing to the west in Gujarat been harvested by erecting bunds and weirs, tribal folk here would have been able to sow and harvest winter crops like wheat, which only a handful of farmers can do today,” says a pensive Gavit.

It was only when the march reached Thane that the farmers received external help, when member of Parliament Eknath Shinde, belonging to the BJP-ally Shiv Sena, offered water and ambulance services.

When the farmers waited at Azad Maidan, the final stop as leaders negotiated terms with cabinet ministers, they were offered the final meal. Jayant Patil of the Peasants and Workers Party of India, and MLA from Raigad crowd-sourced jowar and rice breads (bhakari) and masala-cooked dried fish (sukat)—traditional food plate in coastal Maharashtra—from households in his constituency and shipped them to Azad Maidan.

To commemorate the success, about five to six thousand farmers participated in a victory rally on April 2 in Kalwan, 50 km from Surgana.

“Why do you think a farmer chooses to kill himself instead of voicing his anger in protest? It is because he has lost all hope,” Navle says.

“A farmer deserves to live on his own with dignity, but he cannot fight the quest alone. Only collective action can bring out a change. This long march was one step in that direction”.

As Minal Pawar, who returned to her village a decade ago after graduation, says, “My people did not walk 170 km and got their feet injured for empty promises. Our protest will not stop until all demands are met.”

Source: Why Maharashtra farmers walked 170 km and how their strike played out | Business Standard News