The march was led by the All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS) and lasted six days, during which the farmers marched to the main area of Mumbai and then surrounded the state legislature building (Vidya Bhavan). On 12 March, the protest came to an end after the state government agreed to address the farmers’ demands. Inspired by the events in Maharashtra, farmers in Uttar Pradesh organized a similar march to Lucknow on 15 March, demanding the state government address their dire situation. Some of the farmers’ demands included loan waivers and removing private companies from their lands.

The determined mood in the Mumbai and Lucknow marches can be seen in the fact that many walked barefoot, to the point of having bleeding feet. When questioned first-hand about why they were walking barefoot, some answered back that they could not afford anything but chappals (sandals), which wore out after marching for a few kilometers. Another farmer from the Korat village stated:

“My legs hurt, my entire body aches. Ideally, I would like to go home and sleep on my khatiya [ed – cot]. But how can I give up, considering that the land I have worked on for decades is not even in my name?”

Despite their physical pain and the hot weather, the farmers were determined to continue their struggle, chanting slogans such as “Long Live the Revolution” and “Long Live the Farmers”, and received various kinds of support from the people in the city.

In the Lucknow march (Chalo Lucknow – “Let’s go to Lucknow”), also organized by AIKS, farmers marched down to the city with slogans like “No to Suicide, Unite to Fight,” in reference to the mass suicide rates among farmers across the country. The farmers and protesters alike gathered around Lakshman Mela Maidan, targeting the government for its anti-farmer policies. Some stated that Modi acts like a friend to farmers but has done nothing but give concessions to the banks, making it harder for farmers to take out loans. Furthermore, the protesters stated that the state government’s promises of loan waivers vanished into thin air, and that the actual waivers were as low as 10 or 40 rupees, whereas the claims were as high as a few crores [ed – a unit that denotes 10 million].

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been trying to mobilise support against the marching peasants by calling them a Naxalite conspiracy. Nevertheless, the farmers who marched to Mumbai were able to pressure the Maharashtra’s government Chief Minister, Devendra Fadnavis to promise to transfer tribal rights to the land. Of course words are cheap and there has been no action yet, but this reveals the fear of the ruling class of the pressures building up amongst the masses.

Some of the other demands put forward by the AIKS included opposing giving away “water to Gujarat that rightfully belongs to Maharashtra,” creating committees to assure that these demands are implemented within a matter of months, as well as implementing the schemes that determine prices of farmers’ crops based on a 70:30 ratio. This reveals the contradictory and confused nature of the protests. But it also lays bare the limitations of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) which leads the front. They have targeted Modi’s government for the problem, stating that the administration has “waived loans worth Rs 2.40 lakh crore [ed – 240,000 x 10m] given to rich corporations, but are asking farmers to pay every penny.” However, the AIKS leadership does not take aim against the big business and the capitalist class that rules India.

This falls in line with the general line of the CPI(M) which long ago abandoned genuine Marxism and has degenerated through their parliamentary cretinism and alliances with bourgeois parties. But as the radical turn of the Indian farmers indicates, the land question in India cannot be solved within the framework of capitalism.

The farmers’ protests have revealed the limitations of the CPI (M) / Image: Rcmandota

The farmers’ protests have revealed the limitations of the CPI (M) / Image: Rcmandota

This is not the first time farmers across India have demonstrated for these basic demands. Last November, thousands of farmers in neighboring villages marched down to New Delhi to protest how farmers are driven into severe debt and poverty. The farmers, and representatives from 184 farmers’ organizations, surrounded the nation’s parliament and demanded the government implement a nationwide waiver for crop loans, proper compensation for their produce, and (most importantly) relief from debt. Similarly, earlier last year, thousands of Tamil farmers protested in Jantar Mantar due to the drought in Tamil Nadu, which decimated the farmers’ crop. As a result, there were mass suicides for months after the drought, exacerbated by the fact that neither the central nor state government provided relief funds.

Since the 1960s, there have been mass suicides among farmers across the country. In the rural areas, peasant suicides have become the norm in many parts of India. Since 1995 alone, more than 300,000 farmers have taken their own lives. This figure has steadily risen each year, reaching 12,602 in 2015. In states like Maharashtra, more than 23,000 farmers committed suicide between 2009 and 2015, while in 2015 alone, approximately 12,900 farmers had done so.

To address this suicide epidemic in the country, Modi’s administration invested in a $1.3bn insurance scheme to protect farmers from crop failure. But many of these crop insurance schemes have only created “caps that prevented [farmers] from recouping the full commercial value in case of damage.” Furthermore, $1.3bn isn’t close to solving the problems of the hundreds-of-millions of poor farmers. In reality, the scheme was nothing but a demagogic stunt to prop up Modi’s the right-wing Hindu nationalist party, the BJP, after losing the elections in two states.

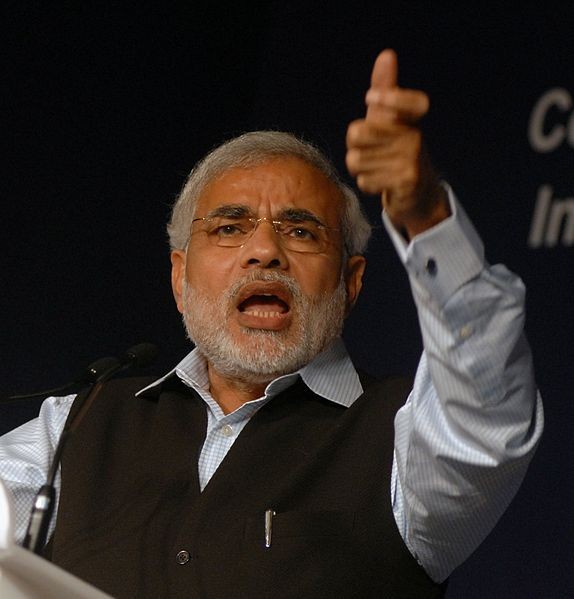

Modi’s administration has brought nothing but misery to the rural poor / Image: World Economic Forum

Modi’s administration has brought nothing but misery to the rural poor / Image: World Economic Forum

The biggest causes of suicides are bankruptcy and debt to banks and micro-finance institutions. More than 72.6 percent of the farmers who committed suicide in 2015 were small farmers who owned less than two hectares of land. Rural India makes up 68 percent – or around 800m – of India’s population. Almost half of the workforce is in agriculture, but the sector only produces around 15 percent of India’s GDP. Around 83 percent of this population are either landless or marginal farmer households owning less than 1 hectare of land. The average amount of cultivable-land per head is less than 0.2 hectares. This has steadily gotten worse with the rising population. Due to lack of jobs in the cities, people have remained in the countryside. Furthermore, a polarisation has taken place, with wealthy families making up 0.25 percent of the rural population sitting on more than 10 hectares of land per person.

The shrinking plots of land are unsustainable, a problem exacerbated by the lack of funds and access to basic infrastructure and modern technology. From 1951 to 2002 the irrigated areas of India only went from 22.6m hectares to 58.1m. According to the World Bank, only about 35 percent of total agricultural land in India was reliably irrigated in 2010. The fact that most rural areas only have patchy access to running water and electricity makes this investment in basic irrigation infrastructure more expensive. Hence, two-thirds of farms are dependent on rainfall for growing crops. The lack of investment has had devastating consequences. In fact, according to the World Economic Forum, labour productivity in agriculture has barely increased since 1970.

The primitive level of agriculture means that when there are droughts, such as the one in 2015, the peasants are helpless to act. Meanwhile, when a particularly good year occurs, such as the one in 2016, these farms suffer equally from falling prices. Rich farms, on the other hand, can guarantee stable crops during droughts and have storage facilities, freezers and refrigerators to offset pricefalls during boom periods. Hence, the rich profit from the fluctuations in market prices during such events, while the poor stand to lose at each turn.

There is a suicide epidemic amongst poor farmers in India / Image: public domain

There is a suicide epidemic amongst poor farmers in India / Image: public domain

The guaranteed buying price that the state has set up for agricultural goods does not benefit small farmers either, who do not have the facilities or the means of transport to take their crops to the state-run centres. The poor farmers are instead forced to sell their produce to middlemen who have developed cartels to push the buying prices as low as possible. The result is that only around 25 percent of the final sale price goes to the peasant, while the rest is divided up between parasitic monopolies who control the market in one way or another.

This leads to a deep economic crisis for the poor peasantry. The subsidy reforms carried out by Modi (which raised the price of fuel and basic goods) is adding to this crisis. To survive, about 52 percent of agricultural households – between 3-400 million people – have had to go into debt, estimated to be on average Rs 47,000 per household. Hundreds-of-millions of farmers and their families are on the verge of bankruptcy and are mercilessly being pushed further into poverty each year. With jobs in the cities already peaking out, there is no way out of their misery.

That is the real basis of the ever-rising wave of suicides. Of course, the “captains of industry”, the BJP and corporate media shed crocodile tears when it comes to writing-off peasant loans. The government stops short of granting serious loan waivers of thousands of crores [ed – tens of billions] to poor farmers, while it at the same time writes off lakhs of crores [ed – trillions] of debt held by large private corporations.

Meanwhile, a layer of farmers who have lost everything, or who have been close to losing it, have taken refuge in the cities that compose the bulk of the shantytown lumpenproletariat roaming the streets aimlessly, vulnerable to easy manipulation by organised crime and demagogues.

The technology is available to lift farmers out of their misery / Image: Pixino

The technology is available to lift farmers out of their misery / Image: Pixino

All of this is just the tip of the iceberg of the daily hell that the Indian rural poor have to go through. The liberal bourgeois shamelessly point the finger at climate change as the biggest culprit. But aside from the fact that capitalism today is itself a great driving force of climate change, they are also trying to hide another fact: modern technology allows for humanity to master nature rather than suffer its unpredictability. That is what distinguishes civilisation from barbarism.

The fact that hundreds-of-millions of Indian peasants are forced to live in similar conditions to ancient primitive societies is a damning indictment of the Indian capitalist class. This leech on an ancient civilisation has proven completely incompetent to carry out the most basic tasks of society.

Hundreds-of-millions of Indian peasants are forced to live in similar conditions to ancient primitive societies / Image: Flickr, Ananth BS

Hundreds-of-millions of Indian peasants are forced to live in similar conditions to ancient primitive societies / Image: Flickr, Ananth BS

At the same time, the anger building up and occasionally surfacing amongst the farmers and peasants carries within it great revolutionary potential, which, if united with the working class, would be an unstoppable force to wipe out the whole rotten establishment once and for all.

This was already shown early on in Modi’s administration, when he went on to the offensive against the peasants by trying to push through an amendment to the Land Acquisition Act of 1894. This amendment would let local municipal corporations grab peasant lands in return for meagre compensation. Here, Modi faced one of his first setbacks, as mass resistance throughout the country forced the government to retreat.

Early on in Modi’s administration he went on to the offensive against the peasants / Image: Al Jazeera

Early on in Modi’s administration he went on to the offensive against the peasants / Image: Al Jazeera

Last June we began to see increasing tensions rising amongst the peasants. Farmers took to the streets in Haryana, Punjab, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu by blocking highways, spilling produce on the streets and clashing with the police, demanding loan waivers and better prices for their produce. Again the government had to take a step back and offer a series of concessions and partial write-offs for the poor peasants’ debts. Of course, that was nowhere near what was needed nor anywhere close to the debt write-offs it issues for the rich and big business.

Modi came to power on the basis of an anti-establishment wave by promising to bring back the so-called “good days” (Acche Din). In 2015, he promised to double farm incomes by 2022 and ensure farmers a 50 percent profit over the cost of production. But nothing good has come out of the Modi regime for the vast majority of Indians, who have only seen more misery.

Meanwhile the rich have been profiting like never before. In 2016, a report by Credit Suisse Research Institute said that the top one percent of the country’s population held 58.4 percent of its wealth, up from 53 percent in 2015. A new study co-written by the famous economist Thomas Piketty puts inequality levels higher than 1921 levels when India was still under British rule. The International Food Policy Research Institute has put India at number 100 out of 109 countries on the Global Hunger Index. As of 2015-16, 21 percent of Indian children were underweight. Not only has this figure not improved for 25 years straight, it is up from 20 percent in 2005-2006.

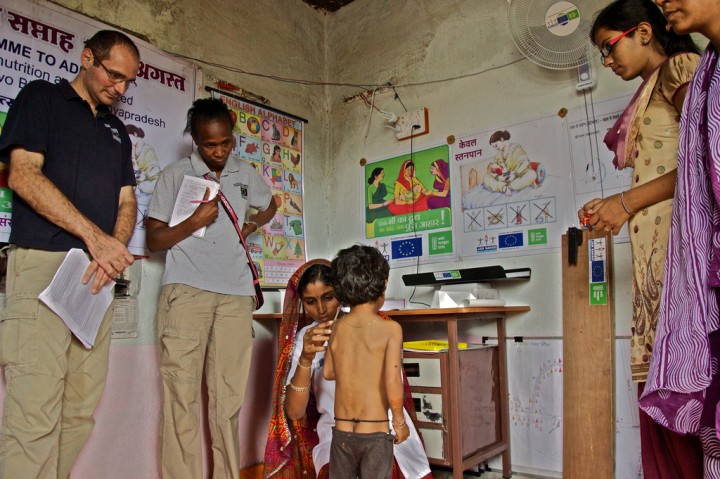

As of 2015-16, 21 percent of Indian children were underweight / Image: Flickr, EUCPHAO

As of 2015-16, 21 percent of Indian children were underweight / Image: Flickr, EUCPHAO

The six-day long march led by tens-of-thousands of farmers in Mumbai shook the entire country and certainly scared the Indian ruling class. It is a sign of the beginnings of the reawakening of the Indian rural masses. In fact, immediately after the farmers ended their recent march, farmers in Uttar Pradesh came out, not only to demand a better standard of living, but directly targeting Modi’s government for its anti-agrarian austerity policies.

To provide what the farmers actually want, including access to their own land without private companies meddling, would mean an attack on the profits of both the private companies and the banks, made through collecting debt. AIKS should call for the abolition of all debt, and not only provide waivers for farmers, but all the resources to allow them access to their lands and produce their crops, and full compensation when droughts occur.

At the same time, it must also fight for a modernisation of Indian infrastructure: expansion of the electricity and communication grid, modern irrigation and water networks, as well as rail, road and highway networks to reach all corners of the country.

But this would necessitate the farmers taking a stand against the bankers and the narrow-minded, parasitic capitalist class, which is incapable of anything but a scorched-earth policy of looting the state and the land resources as quickly and cheaply as possible. While they suck billions of dollars of wealth out of society and close factories en masse, they leave hundreds-of-millions, many with university degrees, to rot in unemployment, or informal, hand-to-mouth type jobs. The only solution for the masses is to fight to take over the banks and industries and to mobilise the millions of unemployed to modernise the country and address the many pressing needs of the workers, the farmers, and the poor. In this struggle, the farmers can only rely on their natural allies in the urban and rural working class.

Inquilab Zindabad! (Long live revolution!) / Image: public domain

Inquilab Zindabad! (Long live revolution!) / Image: public domain

The AIKS leaders should lead the way in connecting the demands of the farmers to the fight for socialism in India, which is the only way to secure their aspirations and bring an end to all of this misery. The massive farmers’ protests are just an example of the strength of the Indian working masses! These events coincide with a time when the working class is also awakening. This can be seen in the exponential growth of annual general strikes over the past several years. The conditions for revolutionary explosions are being prepared in all layers of Indian society and once the masses begin to move, nothing will be able to stop them.

We offer our solidarity with the Indian farmers’ fight for the right to a civilised existence! To echo their own chants: Inquilab Zindabad! (Long live revolution!)