32nd Conference: Report of the Commission on Agricultural Prices

Report of the Commission on Agricultural Prices

Table of Contents

Introduction

The Nasik Conference in January 2006 was held in the backdrop of the continuing agrarian crisis, manifested in a combination of unremunerative prices, rising input costs and increasing indebtedness of the peasantry. Thousands of peasants were committing suicide due to crop failures and the unbearable debt burden. The Commission on agricultural prices in the Nasik Conference had noted that the terms of trade had been moving against agricultural commodities for over a decade.

| Period | 1980-81 to 1990-91 | 1990-91 to 1996-97 | 1996-97 to 2003-04 |

|---|---|---|---|

| % increase per year | 0.19 | 0.95 | -1.69 |

Source: Eleventh Plan Document, Volume III, Chapter 1 (Agriculture)

Since then the situation vis-à-vis agricultural prices have changed to some extent, with a substantial rise in the prices of agricultural commodities across the world, which had its impact in India as well. However, the global food price inflation witnessed in 2007-08 did not translate into higher incomes for the farmers of the developing countries, especially the small and marginal peasants. From the middle of 2008, with the onset of the global recession, food prices have declined from their peaks but have continued to remain above the 2007 levels in 2009 (latest commodity price data from World Bank attached as Annexure I).

Global Food Inflation

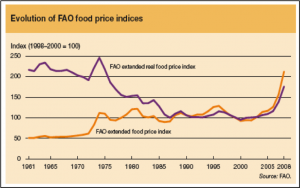

International food prices began to rise in 2006 and steep food price inflation was witnessed throughout 2007 until mid-2008. The surge of food price inflation increased food insecurity and led to violent protests in several countries. The FAO food price index (comprising of 55 food commodities) rose by 7% in 2006 and 27% in 2007, and that increase accelerated in the first half of 2008. Since then, prices have fallen steadily but remain above their longer-term trend levels. The terms of trade also moved sharply in favour of agricultural commodities since 2006.

While almost all agricultural product prices increased, the rate of increase varied from one commodity to another. In particular, international prices of basic foods, such as cereals, oilseeds and dairy products, increased far more dramatically than the prices of tropical products, such as coffee and cocoa, and raw materials, such as cotton or rubber. The price boom was also accompanied by much higher price volatility than in the past, especially in the cereals and oilseeds sectors. In the first four months of 2008, volatility in wheat and rice prices approached record highs. Vegetable oils, livestock products and sugar all witnessed much larger price swings than in the recent past. Such high volatility in food prices was caused by enhanced speculative activities in the commodity futures markets.

This sharp rise in global food prices in 2007-08 has been attributed to several factors. The explanation that food prices have soared because of more demand from China and India is not valid, since per capita consumption of grain have actually fallen in both countries over the past decade. Supply side factors have been more significant. These include the short-run effects of diversion of both acreage and food crop output for biofuel production, as well as more medium term factors such as rising costs of inputs, falling productivity because of soil depletion, inadequate public investment in agricultural research and extension, and the impact of climate change that have affected harvests in different ways.

- Bio-FuelsIncreasing international oil prices and government subsidies in the US, Europe, Brazil and elsewhere to promote biofuels as an alternative to petroleum, has led to significant shifts in acreage to the cultivation of crops that can produce biofuels, and diversion of such output to fuel production. For example, in 2007 the US diverted more than 30 per cent of its maize production, Brazil used half of its sugar cane production and the European Union used the greater part of its vegetable oil seeds production as well as imported vegetable oils, to make biofuel. In addition to diverting corn output into non-food use, this has also reduced acreage for other crops and has naturally reduced the available land for producing food.

- Neoliberal PoliciesThe prolonged agrarian crisis in many parts of the developing world has been largely a policy-determined crisis, resulting from the neoliberal framework that has governed economic policymaking in most countries over the past two decades. One major element has been the lack of public investment in agriculture and in agricultural research. This has resulted in low to poor yield increases, especially in tropical agriculture, and falling productivity of land. Greater trade openness and market orientation of farmers have led to shifts in acreage from traditional food crops to cash crops that have increasingly relied on purchased inputs. At the same time, both public provision of different inputs for cultivation and government regulation of private input provision have been progressively reduced, leaving farmers to the mercy of private input dealers. As a result, prices for seeds, fertilisers and pesticides have increased quite sharply.There have also been attempts in most developing countries to reduce subsidies to farmers leading to higher power and water prices, thus adding to cultivation costs. Costs of cultivation have been further increased in most developing countries by the growing difficulties that farmers have in accessing institutional credit, because financial liberalisation has moved away from policies of directed credit and provided other more profitable opportunities for financial investment. So many farmers are forced to opt for much more expensive informal credit networks that have added to their costs. In addition, the ecological implications of both pollution and climate change, including desertification, depletion of ground water and loss of cultivable land, are issues that have been ignored by policy makers in most countries. All these have had negative effects on global food production and availability.

- SpeculationThe wild swings in food prices in 2007-08 were also the result of heightened speculative activity in commodity futures markets. Financial deregulation gave a major boost to the entry of new financial players (like the hedge funds) into the commodity exchanges. Unlike producers and consumers who use such markets for hedging purposes, financial firms and other speculators increasingly entered the market in order to profit from short-term changes in price. The resulting price volatility had very adverse effects on both cultivators and consumers of food. This sent out confusing, misleading and often completely wrong price signals to farmers while the consumers suffered due to food price inflation. The main gainers from this process were the financial intermediaries who were able to profit from rapidly changing prices.

- Rising Input CostsAgricultural input costs shot up dramatically in 2007, outpacing output prices. The dramatic increase in oil prices that began in 2003 has had a profound effect on all economic sectors, including agriculture. Increases in fuel prices have raised the costs of producing agricultural commodities both directly by raising the cost of far power and transport, but also indirectly because oil is an important cost item in fertilizer production. The price of some fertilizers rose by more than 160 percent in the first few months of 2008 compared with the same period in 2007. This rate of increase in the price of fertilizer was greater than the rate of increase in prices for agricultural products.

Small Peasants Have Not Benefited: The important aspect of the global increase in agricultural prices since 2007 is that the small and marginal peasantry has not benefited anywhere. The FAO has noted (The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets 2009):

Producers in developing countries have faced real declines in prices in most of the last 50 years. The result has been a lack of investment in agriculture and stagnant production. These formed the background to the recent problems in international food system and they also made it more difficult for developing countries to deal with these problems. So, on the face of it, the high food prices, and the possibility that they might persist (even if not at the peak levels reached in early 2008), looked like an opportunity for small poor producers. But was it?…Most developing country producers are far distanced from what happens on international markets, so increasing food prices there do not necessarily mean higher prices for poor producers. For this to be the case, those high international prices need to be transmitted across national borders and through marketing chains. However, higher output prices alone are still not sufficient. Incentives to invest and produce also depend on how much the costs of inputs such as seeds and fertilizers have risen. Producers need access to affordable inputs. They also need access to affordable credit. Even where adequate incentives are in place, a positive supply response from producers can be blocked by a range of supply-side constraints, especially a lack of transport and market infrastructure for bringing any increase in production to market. In many developing countries, none of these conditions is adequately met. As a result, higher prices on international markets have not triggered a positive supply response by smallholder farmers in developing countries.

For developing countries like India, it is not only the case that the small peasants are unable to take advantage of high international prices because of lack of integration with markets and their dependence on middlemen and big traders for marketing their produce. Most small peasants and agricultural workers are also net buyers of food. Therefore they suffer from steep rise in food prices. The main beneficiaries of the steep increase in international food prices have been the giant agribusiness corporations, MNCs trading in agricultural inputs like fertilisers and seeds and the financial speculators in the commodity futures markets.

Agricultural Prices in India

In the backdrop of the steep rise in international food prices, the agricultural prices in India too have seen an upward trend over the past three years. The MSPs for foodgrains like wheat, paddy, other cereals and pulses were raised to some extent, especially in 2008-09, which was an election year. The MSPs for wheat and paddy were Rs. 630 and Rs. 560 per quintal respectively, in 2004-05. The pressure of the peasant movement and the Left Parties on the UPA-I Government played a role in the increase in the MSPs effected in this period.

| Commodity | MSP 2008-09 (crop year) | Commodity | MSP 2008-09 (crop year) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kharif crops | Rabi crops | |||||

| Paddy (common) | 850+ Rs. 50 per quintal bonus | Wheat | 1080 | |||

| Paddy (Gr. A) | 850+ Rs. 50 per quintal bonus | Gram | 1730 | |||

| Jowar (Malindi) | 860 | Masur (lentil) | 1870 | |||

| Maize | 840 | Rapeseed/mustard | 1830 | |||

| Arhar (Tur) | 2000 | Barley | 680 | |||

| Moong | 2520 | Other crops | ||||

| Cotton (F-44/H-777,J34) | 2500* | Sugarcane | 81.18 | |||

| Groundnut in shell | 2100 | |||||

| * staple length (mm) of 24.5-25.5 and Micronaire value of 4.3-5.1 | ||||||

Source: Economic Survey, 2008-09

| Commodity | MSP 2009-10 (crop year) | Commodity | MSP 2009-10 (crop year) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kharif crops | Rabi crops | |||||

| Paddy (common) | 950+ Rs. 50 per quintal bonus | Wheat | 1100 | |||

| Paddy (Gr. A) | 950+ Rs. 50 per quintal bonus | Gram | 1760 | |||

| Jowar (Malindi) | 860 | Masur (lentil) | 1870 | |||

| Maize | 840 | Rapeseed/mustard | 1830 | |||

| Arhar (Tur) | 2300 | Barley | 750 | |||

| Moong | 2760 | Other crops | ||||

| Cotton (F-44/H-777,J34) | 2500* | Sugarcane | 129.84 | |||

| Groundnut in shell | 2100 | |||||

| * staple length (mm) of 24.5-25.5 and Micronaire value of 4.3-5.1 | ||||||

Source: Economic Survey, 2009-10

The neoliberal policies pursued by successive Governments at the Centre had considerably weakened food self-sufficiency since the decade of 1990s. There has been an increasing reliance on imports by the Government, often at exorbitant prices, not only for edible oils and pulses but also for items like wheat (in 2006 and 2007) and sugar (in 2009). The increase in MSPs for crops was necessitated in this backdrop. The short-term response of agricultural output, especially foodgrains production, to the increase in MSPs was positive. Agricultural growth averaged over 4.9% between 2005-06 and 2007-08 and total foodgrains production recorded an annual average increase of around 10 million tonnes during this period.

| Grains | 2001-02 | 2002-03 | 2003-04 | 2004-05 | 2005-06 | 2006-07 | 2007-08* | 2008-09@ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Foodgrains | 212.90 | 174.78 | 213.19 | 198.36 | 208.60 | 217.28 | 230.78 | 229.90 | ||||||||

| A. Cereals | 199.48 | 163.65 | 198.28 | 185.23 | 195.20 | 203.08 | 216.02 | 215.70 | ||||||||

| – Rice | 93.34 | 71.82 | 88.53 | 83.13 | 91.79 | 93.35 | 96.69 | 99.40 | ||||||||

| – Wheat | 72.77 | 65.76 | 72.15 | 68.64 | 69.35 | 75.81 | 78.57 | 77.60 | ||||||||

| – Coarse Cereals | 33.37 | 26.07 | 37.60 | 33.46 | 34.06 | 33.92 | 40.76 | 39.96 | ||||||||

| B. Pulses | 13.37 | 11.13 | 14.91 | 13.13 | 13.39 | 14.20 | 14.76 | 14.25 | ||||||||

| C. Oilseeds$ | 20.62 | 14.84 | 25.19 | 24.35 | 27.98 | 24.29 | 29.76 | 28.10 | ||||||||

| * Final estimates | ||||||||||||||||

| @ Third advance estimates | ||||||||||||||||

| $ Includes Groundnut, Castorseed, Sesamum, Nigerseed,Rapeseed&Mustard,Linseed,Safflower,Sunflower and Soyabean | ||||||||||||||||

Source: Directorate of Economics and Statistics

However, the fact that the increase in support prices and other agricultural policies of the UPA-I Government were very limited was borne out by the slowing down of agricultural growth in 2008-09 to 1.6%. Foodgrains production in 2008-09 not only fell short of the 233 million tonnes target but was also lower than the 2007-08 output. This year, the severe drought that has afflicted over 300 districts (alongwith floods in some districts) has already taken a further heavy toll on crop production.

Present Situation

In 2009-10, foodgrain production in the kharif season is projected to fall by 16% over last year. A rainfall deficit of 23% in the 2009 monsoon season and drought in many states led to a 5.3% fall in acreage. The delayed withdrawal of the southwest monsoon will benefit rabi crops. But this will not be enough to make up for the loss in kharif production. (Advance Estimates of Production of foodgrains, oilseeds and other commercial crops for 2009-10 released by the Department of Agriculture and Cooperation provided in Annexure II).

Kisan Sabha Demand for Higher MSPs

It needs to be noted that even though some increase in the MSPs were effected under UPA-I Government, the increases fell far short of the recommendation of the National Commission of Farmers (NCF) that “the MSP should be at least 50% more than the weighted average cost of production”. Moreover, the estimated costs of production taken into account are far below the actual expenses incurred by the peasants. Going by the Government’s calculations, the MSPs for only three crops; paddy, wheat and rapeseed-mustard; are above the 50% cost-plus level. In cotton, maize, groundnut, musur, bajra, arhar and urad, the MSPs now are 20-30% above C2 and in others between 10-20%. In view of this the AIKS placed its proposals for higher MSPs for 2009 kharif crops before the Commission on Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) in March 2009 (attached as Annexure III).

Besides higher support prices, the timely fixation of MSP is also a major issue. In India, kharif crops, which are sown between June and September, account for more than half of the total grains production. The CACP is required to convey its recommendations to the Government well before the sowing season of the crop. However, the MSP fixation is usually announced only by the time of harvest. The small and marginal farmers are thereby forced to make distress sales and also sell at below MSP to private dealers. In view of this, the Kisan Sabha has proposed that the MSP must be mandatorily announced well before the crop-sowing season in June.

Strengthening Public Procurement

The National Policy for Farmers drafted by the NCF and finalised in October 2006 had made several important recommendations regarding public procurement and distribution. It is worthwhile to reiterate the key recommendations of the NCF in this regard:

- What farmers seek is greater protection from market fluctuations. Important steps needed are:

- The Minimum Support Price (MSP) mechanism has to be developed, protected and implemented effectively across the country. MSP of crops needs to keep pace with the rising input costs.

- The Market Intervention Scheme (MIS) should respond speedily to exigencies especially in the case of sensitive crops in the rainfed areas.

- The establishment of Community Foodgrain Banks would help in the marketing of underutilized crops and thereby generate an economic stake in the conservation of agro-biodiversity.

- Indian farmers can produce a wide range of health foods and herbal medicines and market them under strict quality control and certification procedures.

- The Public Distribution System (PDS) should be universal and should undertake the task of enlarging the food security basket by storing and selling nutritious millets and other underutilized crops.

- The twin goals of ensuring justice to farmers in terms of a remunerative price for their produce, and to consumers in terms of a fair and affordable price for staples (65% of consumers are also farmers) can be achieved through the following integrated strategy:

- The MSP and procurement operations are two separate initiatives and should be operated as such. The Government needs to ensure that both the farmers (who also constitute the majority of consumers) and the urban consumers get a fair deal. Due care should be taken of the cost escalation after the announcement of the MSP in its operationalisation. The Government should procure the staple grains needed for the PDS at the price private traders are willing to pay to farmers. Thus, the procurement prices could be higher than the MSP and would reflect market conditions. The MSP needs to be protected in all the regions across the country.

- The food security basket should be widened to include the crops of the dry farming areas like /*bajra*, jowar, ragi, */*minor millets and pulses. The PDS should include these nutritious cereals and pulses purchased at a reasonable MSP. This will be a win-win situation both for the dryland farmer and the consumer. *We will witness neither a second green revolution nor much progress in dryland farming unless farmers get assured and remunerative prices for their produce. * #+ENDQUOTE

- Both universal PDS and enforcing MSP throughout the country for the selected crops are essential for imparting dynamism to agriculture.”

- The Commission on Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) should be an autonomous statutory organization with its primary mandate being the recommendation of remunerative prices for the principal agricultural commodities of both dry-farming and irrigated areas. The MSP should be at least 50% more than the weighted average cost of production. The “net take home income” of farmers should be comparable to those of civil servants. The CACP should become an important policy instrument for safeguarding the survival of farmers and farming. Suggestions for crop diversification should be preceded by assured market linkages. The Membership of the CACP should include a few practicing farmwomen and men. The terms of reference and status of the CACP need review and appropriate revision.

Most of these recommendations were not implemented by the UPA-I Government. Public procurement continues to remain limited to a few major crops and procurement operations are carried out only in limited parts of the country. Bulk of the small peasants do not benefit from public procurement. MSP excludes important crops like chilly, areca nut, spices, castor, other oilseeds, aromatics, cash crops, traditional staples etc, thereby leaving their producers at the mercy of private traders. Strengthening and expanding public procurement remains to be a major issue before the Kisan Sabha.

Timely procurement is also a major issue. The delay in procurement and inability to procure sufficient quantity has often forced the cultivators to sell their produce at low prices to private traders to meet their day to day expenses as well as to meet the requirement of initial investment for the next season. The Kisan Sabha has demanded that the Food Corporation of India as well as other Governmental agencies involved with procurement should stay and involve with procurement for a longer period. Timely procurement should be complemented by an adequate storage mechanism so that market prices do not fall below the MSP. There is hence a need for augmentation of Storage Facilities.

Food Inflation and Universal PDS

Food price inflation in India has risen to very high levels. Measured by wholesale price index, annual inflation in food articles was over 17.5 % in February 2010 (Latest WPI inflation figures in Annexure IV). The rise in prices of vegetables, pulses and cereals are particularly sharp. In terms of consumer price indices, India has the highest inflation rate among all the G 20 countries. The Government has been publicly stating that the reason for food price inflation is because crop prices for farmers have been increased. Such pronouncements, besides concealing the real situation being faced by the peasantry also seeks to divide the people and drive a wedge between the peasants and other sections of the working people. Bulk of the Indian peasantry is a net buyer of food. They are also suffering due to the steep rise in food prices. The main reasons behind high inflation, especially rising food prices are fourfold: (i) neoliberal policies causing agrarian crisis and eroding food self-sufficiency, (ii) weakening of the Public Distribution System (PDS), (iii) failure to check hoarding and speculation and (iv) increase in fuel prices. All these are outcomes of the neoliberal policies pursued by the Congress led Government as well as the erstwhile BJP led NDA Government.

The biggest blow to the PDS came with the introduction of the targeting system in 1996, which made people’s entitlement to cheap food contingent upon the official poverty estimates. The current average national poverty line according to the Planning Commission is only around Rs. 11.80 per person per day for rural areas and Rs. 17.80 per person per day for urban areas. Everyone above these meager income levels are considered to be Above Poverty Line (APL) and therefore excluded from access to subsidised food. This has meant over half of agricultural labourers in India as well as half of dalit and adivasi households are excluded from the BPL category. This faulty policy of dividing the beneficiaries into APL/BPL/Antodaya and other categories, besides excluding a large number of deserving poor, has also led to unviability and closure of several PDS outlets, thus further shrinking its coverage. The weakening of the PDS has deprived people of any relief in the backdrop of the steep rise in the prices of essential commodities.

The Government’s proposed Food Security legislation will be only for BPL cardholders, ensuring 25 kg of foodgrains (rice and wheat) to all BPL families at Rs. 3 per kilo. The total number of BPL families at present is 6.52 crore, which the Government proposes to cut down to 5.91 crore. Antodaya benefits will be eliminated and Antodaya cardholders who at present are getting foodgrains at Rs. 2 per kg will have to pay Rs. 3 per kilo. For both BPL and Antodaya cardholders the quota will be cut by 10 kg per family from the present 35kg to 25 kg. No foodgrain will be allocated for APL sections. Not only will the APL subsidy be eliminated but the APL category will also be cancelled. The proposed law would therefore mean a higher level of exclusion and actually squeezing whatever people are getting today.

The only effective way to ensure food security and providing genuine relief to the people against price rise and inflation is to reintroduce the universal PDS and bring about a massive expansion of PDS outlets. Moreover, besides foodgrains, sugar, pulses and edible oils should be supplied through the PDS in cheap rates.

Besides universalisation of the PDS, the following steps need to be taken by the Government to check price rise and inflation:

- A coordinated countrywide crackdown on hoarding of essential commodities should be launched. Disclosure of stocks of essential commodities by private traders, especially the big corporates, should be made mandatory across the country.

- Futures trading on essential commodities like wheat, potato and some pulses which are still being allowed should be banned forthwith.

- Prices of diesel and petrol should be brought down by cutting excise duties.

Sugarcane Prices

In the past, the Union Government announced Statutory Minimum Price (SMP) for purchase of sugarcane by sugar mills. The major sugar growing States, in view of specific conditions, announced a State Advisory Price, which was usually substantially higher than the SMP. The Union Government also announced a levy price for purchase of levy sugar from sugar mills for the purpose of public distribution. This levy price was determined on the basis of SMP.

In a recent judgement, the Supreme Court has asked the union government to fix the levy price on the basis of the SAP rather than the SMP. In order to avoid the burden of paying a higher levy price, and arrears on account of this, the Union Government brought the Essential Commodities (Amendment and Validation) Ordinance (later passed as a Bill in the winter session of parliament), through which the Government sought to bring about changes in sugarcane pricing to the detriment of the farmers. The ordinance sought to replace the statutory minimum price (SMP) with a new category called fair and remunerative price (FRP). The Union Government argued that if States announced a SAP over and above FRP, they would be required to pay for the difference in levy price on account of higher SAP.

This would have two important implications. First, it would result in erosion of power of State governments to influence prices of sugarcane. Secondly, since State governments would be required to bear the additional financial burden, the States would be inclined to not announce SAP. It is noteworthy that prices of sugar have gone up steeply in the recent years resulting in a sharp increase in profits of sugar mills. Instead of instituting a mechanism that would make sugar mills share these additional profits with sugarcane farmers, the new mechanism has threatened to depress prices of sugarcane. In view of this, the Kisan Sabha demands that the system of announcing SAP by the States should be restored and the Central government should ensure that the additional burden of levy on account of SAP is borne by the sugar mills and not by sugarcane farmers.

ASEAN FTA

The Free Trade Agreement which the Central Government has signed with the ASEAN countries will seriously affect the farmers cultivating coconut, tea, coffee, pepper etc. as well as the large fishing community in states like Kerala, Karnataka, Tamilnadu and the North-Eastern region. The ASEAN FTA, which has already come into effect from 1st January 2010, envisages total elimination of tariffs on a reciprocal basis on about 3200 products by December 2013 while tariff on remaining 800 products will be brought down to zero or near zero levels by December 2016. This will cover more than 80 per cent of the goods that are traded between India and ASEAN.

The Agreement also has identified certain products as Sensitive, Highly Sensitive and products to be put in the Negative List. The Government claims that this will provide protection for the products mentioned in the negative list, which contains 489 items which includes 303 items of agricultural sector, 81 items of textile sector, 50 items of auto sector and 17 items of chemical sector. The reports show that certain marine products – coconut, cashew, vanilla, nutmeg, coriander, cardamom, ginger, turmeric, copra, coconut oil, tobacco, natural rubber, certain items of textiles and auto products are in the negative list. For products not in the Negative list, duties will be reduced in a phased manner and brought to zero by 2019. On 5 items – Tea, Coffee, Pepper, Crude Palm Oil (CPO) and Refined Palm Oil (RPO) which are on the Highly Sensitive list there will be a partial duty cut in 2009. Duty on Tea and Coffee will be brought down to 45%, Pepper to 50% and for CPO and RPO it will be brought down to 37.5% and 45% respectively.

The tariff reductions will be made from the prevalent 2005 rate. The prevalent rate for crude palm oil is 80 per cent, for refined palm oil is 90 per cent, for coffee and black tea is 100 per cent, for pepper is 70 per cent. As per India’s commitment for tariff reduction by 2019, the tariff rate of crude palm oil will be reduced to 37.5 per cent, for refined palm oil to 45 per cent, for tea and coffee 45 per cent, and for pepper 50 per cent. Normally, in trade negotiations and also at the WTO level trade negotiations, all tariff cuts are based on bound levels of tariff rates and not on applied levels. The bound tariff rate for palm oil is 300 per cent, raw coffee stands at 100 per cent, all other forms of coffee at 150 per cent, raw pepper stands at 100 per cent and crushed and ground pepper stand at 150 per cent and tea at 150 per cent. The bound tariff rates show the magnitude of the reduction made on these products.

The implications of the FTA are bound to be severe, given the fact that our country is characterised by low levels of productivity and also exorbitant costs of cultivation. This will make it near impossible for our farmers to compete against the cheap imports. The productivity level of many of the crops is far higher in many ASEAN countries. Pepper productivity in Kerala is around 320 kg per hectare while Vietnam produces 1.2 tonnes and Indonesia 2.3 tonnes per hectare. Productivity of coffee in India stands at 765 kg per hectare while Vietnam produces 1.7 tonnes per hectare. In such a situation, the reduction of tariff rates will increase import from ASEAN countries and effect steep fall in prices of agricultural crops.

Charter of Demands:

- Ensure Stable and Remunerative Prices with Effective ProcurementImplement Dr.Swaminathan Commission Recommendation of C2+50 percent for computing MSP as the base price. Set up Price Stabilisation Fund to protect Farmers from volatile World Market Prices.

- Ensure Timely fixation of MSP and Expand Public Procurement OperationsIt must be made mandatory for the Government to announce the MSP well before the sowing season. Food Corporation of India as well as other Governmental agencies involved with procurement should stay and involve with procurement for a longer period. Public procurement mechanism must be extended across the country and mobile procurement units in far-flung areas must be ensured. Allow procurement through Panchayats and State Corporations and provide incentives to encourage such efforts.

- Widen Crop Basket under the Purview of CACPInclude important crops like coarse cereals (jowar, bajra etc) chilly, potato, areca-nut, spices, oilseeds, jute, dry fruits, aromatics, cash crops, traditional staples, horticultural crops etc under purview of CACP. Ensure Remunerative MSP and effective procurement of Minor Forest Produce, dairy products, poultry and fisheries.

- Provide Incentives For ProductionSubsidised inputs of a superior quality should be guaranteed and production bonuses should be provided.

- Strengthen Public Distribution SystemAn effective procurement mechanism complemented by a Universal Public Distribution System is indispensable if the farmers have to be led out of the present crisis.

- Augment Storage FacilitiesEnsure adequate storage mechanism to ward off problems arising out of erratic climatic conditions. Ensure modern storage facilities and also cold storage facilities.

- Restore Quantitative Restrictions and Ensure Effective Protection From ImportsThe unrestricted import of agricultural products under the free-trade regime is hitting the farmers growing commercial crops like coconut, oil-seeds, tea, coffee and spices. There have to be restrictions imposed on such imports.

- Regulate Markets and Speculative TradingBan all futures trading in agricultural products. Regulate Mandis/Markets to stop exploitation of farmers. Encourage Farmers’ Cooperatives and revamp Commodity Boards/Marketing Boards. Curb Middlemen by directly procuring from farmers. Check hoarding and black-marketing.

- Develop Agro-Based IndustriesAgro-based industries must be developed and jute, cotton, coconut, rubber-based products should be promoted and value addition must be ensured even for Minor Forest Produce.

- Clear Arrears of Sugarcane FarmersSugar Mills are accumulating huge arrears in payment to farmers. They must be paid with interest before the next crushing season.